I’ll never be able to sing “Sleigh Ride” again! Ever! Not even with Amy Grant. Currier & Ives!? Puh-lease! I’ll take Norman Rockwell any day. ANY day.

In 1857, Nathaniel Currier, a Massachusetts lithographer, and James Merritt Ives, a self-trained artist and bookkeeper for the business of N. Currier, formed a partnership. The result was the firm of Currier & Ives, which produced three to four prints every week for fifty years – a total of over 7,500 titles. The lithographs produced by the company were published by Currier & Ives, none were actually drawn or lithographed by them. Upon their deaths in 1888 and 1895 respectively, their sons, Edward West Currier and Chauncy Ives, directed the firm until its close in 1907 (American Historical Print Collectors Society).

Previous to the Emancipation Proclamation, Currier & Ives generally depicted blacks as individuals content with their lives and position in society; they were often pictured in the background of idyllic plantation images. Initially after the Proclamation was issued, the firm continued to depict blacks in a positive light, focusing more on individuals, publishing portraits of John Brown, Frederick Douglas, and black Union soldiers fighting for their freedom (222). As time went on, however, and the freedmen began to move north into the cities, it became more apparent that not all Northerners were unanimous in their support of emancipation and the status of the freedman. The political images published by Currier & Ives during this time were vicious attacks against the character and intelligence of blacks, depicting them as unsupportive and disobliging of the political figures who sought to free them, such as Abraham Lincoln, Horace Greeley, and Senator Charles Sumner (226).

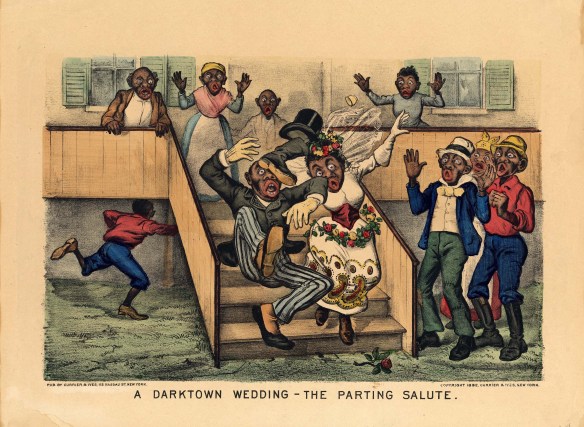

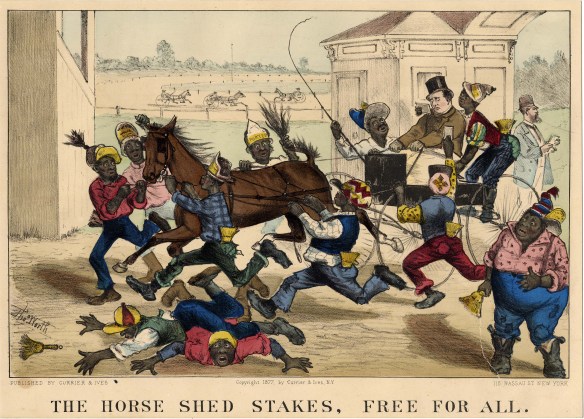

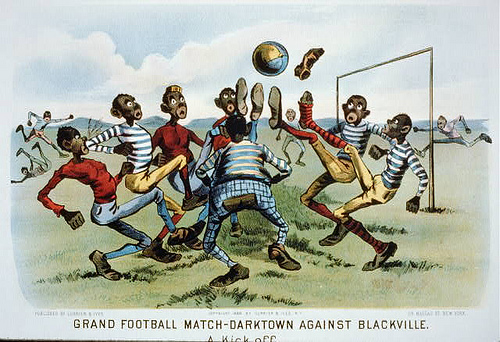

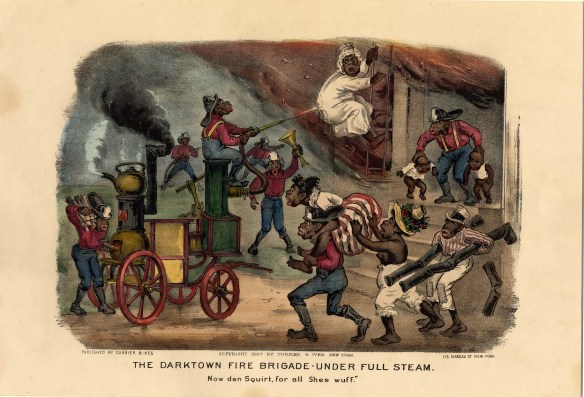

During and after Reconstruction, Currier & Ives, and America it seems, continued to appreciate these negative images of African Americans. Out of this, between the mid-1870s to the early 1890s, the Darktown Comics arose, mostly illustrated by Thomas Worth (1834-1917) and James Cameron (1828-1963). The company described the Comics as “pleasant and humorous designs, free from coarseness or vulgarity, being good natured hits at the popular amusements and excitements of the times”. It has been suggested that Darktown may have “served as satires on polite white behavior as well”, as could be supported by previously positive images of African Americans. Regardless of intent, the prints only reinforced negative racial stereotypes throughout the country.

The caricatures presented by the Darktown Comics consisted of “African Americans performing actions that were more or less normal for ‘ordinary’ folk, meaning whites…the implication being that the African Americans could not execute even the simplest tasks of everyday life without making themselves appear ridiculous”. The most common images depicted by Currier & Ives’ artists were of African Americans attempting to have horse, skull, and sulky races; ride in carriages and yachts; hunt; host lawn parties; play tennis; and fight fires–always with disastrous results. And the depiction of African American lawyers, doctors and the clergymen as bumbling and dishonest were quite malicious. African American children were also featured in a poor light – as mischievous, out of control, disrespectful hoodlums. This is evident in prints by Thomas Worth such as “A Put Up Job” and “A Fall from Grace” (1883) and “Breaking In: A Black Imposition” and “Breaking Out: A Lively Scrimmage” (1881).

African American stereotypes that still exist today were begun here – the connection of African Americans to music, in Darktown specifically of banjo playing, and of their supposed eating habits, most notable in the Comics, that of eating watermelon. This can be seen in the prints that make up the set of the Darktown Banjo Class and in single prints like “O Dat Watermillion!”. As one can see, African American speech was attacked as well, through phonetic renderings steeped in the distortion of stereotypes and caricature.

The Darktown Comics did not develop or exist in a vacuum, however. In addition to theDarktown prints that came out of this time, Harper’s Weekly featured the Blackville prints; examples of which can be seen at HarpWeek’s exhibition, “Toward Racial Equality:Harper’s Weekly Reports on Black America, 1857-1874“ or the Philadelphia Print Shop’s“Blackville Prints.” These were similar in content to Darktown—spoofs of African American attempts at high fashion, sports, etc. The most prevalent artists of this series were Sol Eytinge, Jr., William Ludwell Sheppard, S.C. McCutcheon and “Sphinx” (Philadelphia Print Shop, Ltd.). Other publications, such as Life, Puck and Judge, as well as Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal produced similar images but these were in the context of satire (Hays). Whether or not these images were taken as satire or at face value by the American populous is up for debate, however. Other news and editorial magazines, such as The Outlook and The Independent, also promoted these types of images through their illustrations and advertising—exemplifying the prevalence and acceptance of these racist stereotypes across the country (Hays).

The “high art” of this time, specifically that of southern artists, furthered these stereotypes as well, dehumanizing the African American through their depictions of coal black skin, thick red lips, oversized teeth, and patchwork clothing. It wasn’t until the impact of the Ashcan Society and the period of realism came into play that classical forms of art began to celebrate the figure of the African American as he really appeared. The art of Robert Henry, George Luks, and George Wesley Bellows are forefathers of this new view – a celebration of the African American.

Wow, Tiffany. This is some pretty disturbing stuff.

To me, it speaks to the insecurity of the “artists”, for lack of a better term, and to the deep-seated hatred that motivates so many — then as well as now. Ray

it’s good that you continuously show this so that we will never forget the origin of all the ignorance that we face even today…

those pictures made me want to cry.

its hard to have to reconcile with an evil past that educators and america itself wants to hide and suppress. I am hoping to become a history teacher…i am hoping that i can sneak some real truth into my classes and not just the positive “patriotic” garbage we already have to learn in schools.

These prints were meant to portray black people in a positive way? I wonder what the negative portrayals showed!

Talk about racism then, try being a white person and walk through any housing projects nowadays! That is where true racism lives!

Actually the way the pictures portray black people over a hundred years ago, it is similar to the way black comedians make fun of white people in their stand up today lol!

First thanks for posting truth, I to prefer not to hide any of our past. However, we must not be to ashamed and merely use these as further enlightenment for ourselves. To continue to condemn our own heritage’s actions is futile. Yes learn from it a move on. I believe we have actually pushed so far down that road of condemnation that we have assisted in our own racial attacks. Fueling the fire as it were. Taking it to far, we cannot be held accountable for the actions of our ancestors, we must become the true human and embrace improvement now not yesterday.

I love this shit.

Reblogged this on Speaknic.